A. The Demand and Supply of Cobalt

The 1800s encompass a fascinating period of history full of war and inventions. Napoleon was fighting the Britons and the Austrians, while at the same time the Electric Revolution was going strong with people now talking about storing electricity in what we now know as electric batteries.

It didn’t take long for batteries to find their place in cars as well - in 1828 Hungarian Ányos Jedlik would come up with a mock-up model car powered by a non-rechargeable battery. What was back then an extremely impractical idea, is now making strides to become part of a promising solution of some of today’s most pressing problems. The solution in question - Electric Vehicles (EVs).

To understand the economics surrounding electric vehicles, we first need to take a quick dive into the anatomy of the modern battery cell.

The modern lithium battery consists mainly of nickel, cobalt and lithium. All of those metals play a specific role in the chemistry of the battery - lithium ions flow between the graphite-containing anode and the nickel-containing cathode, while cobalt ensures less overheating and thus more range and durability.

Each metal among those has its fair share of problems within the supply chain. However, while nickel’s mine production is fairly well distributed across the globe (Indonesia 30%, Philippines 13%, Russia 11%) and lithium’s extraction is situated in countries like Australia and Chile and is deemed “relatively more secure”, the mine production of cobalt poses unique problems.

Cobalt is the metal everyone seems to be talking about. The supply chain encompassing cobalt extraction and refinement is problematic because of numerous geopolitical reasons, mainly concerning the Democratic Republic of the Congo and China. Throughout the article we will be referring to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as the DRC or simply Congo (not to be confused with the Republic of the Congo, which plays little part in this piece).

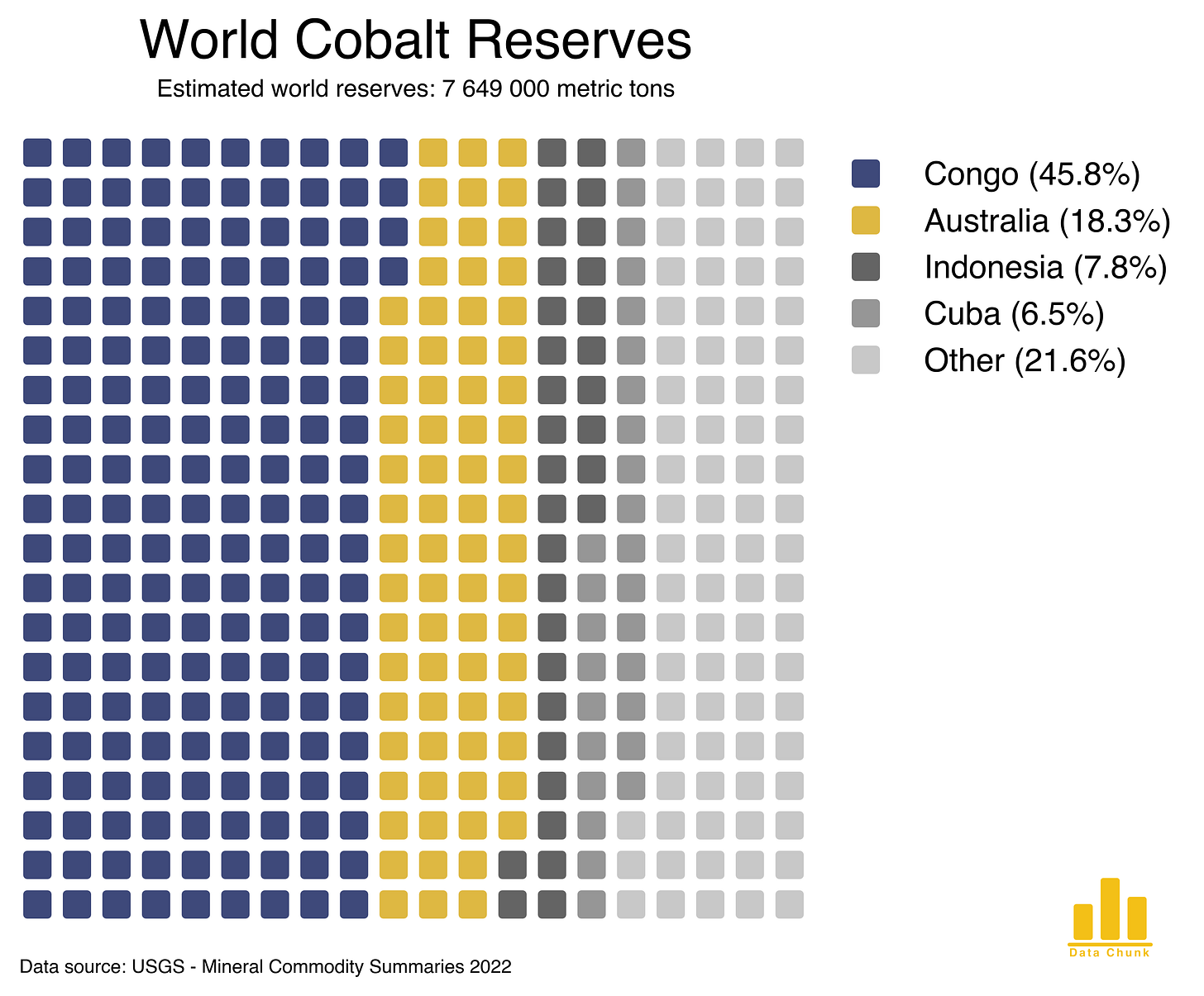

Cobalt is for the most part obtained as a by-product of nickel and copper mining. The DRC holds a huge amount of the world’s cobalt reserves and is also among the top copper exporters, which coupled with little government regulation, a cheap workforce and low standard of living (among the bottom when it comes to GDP per capita) makes the industry a lucrative one for Western EV manufacturers.

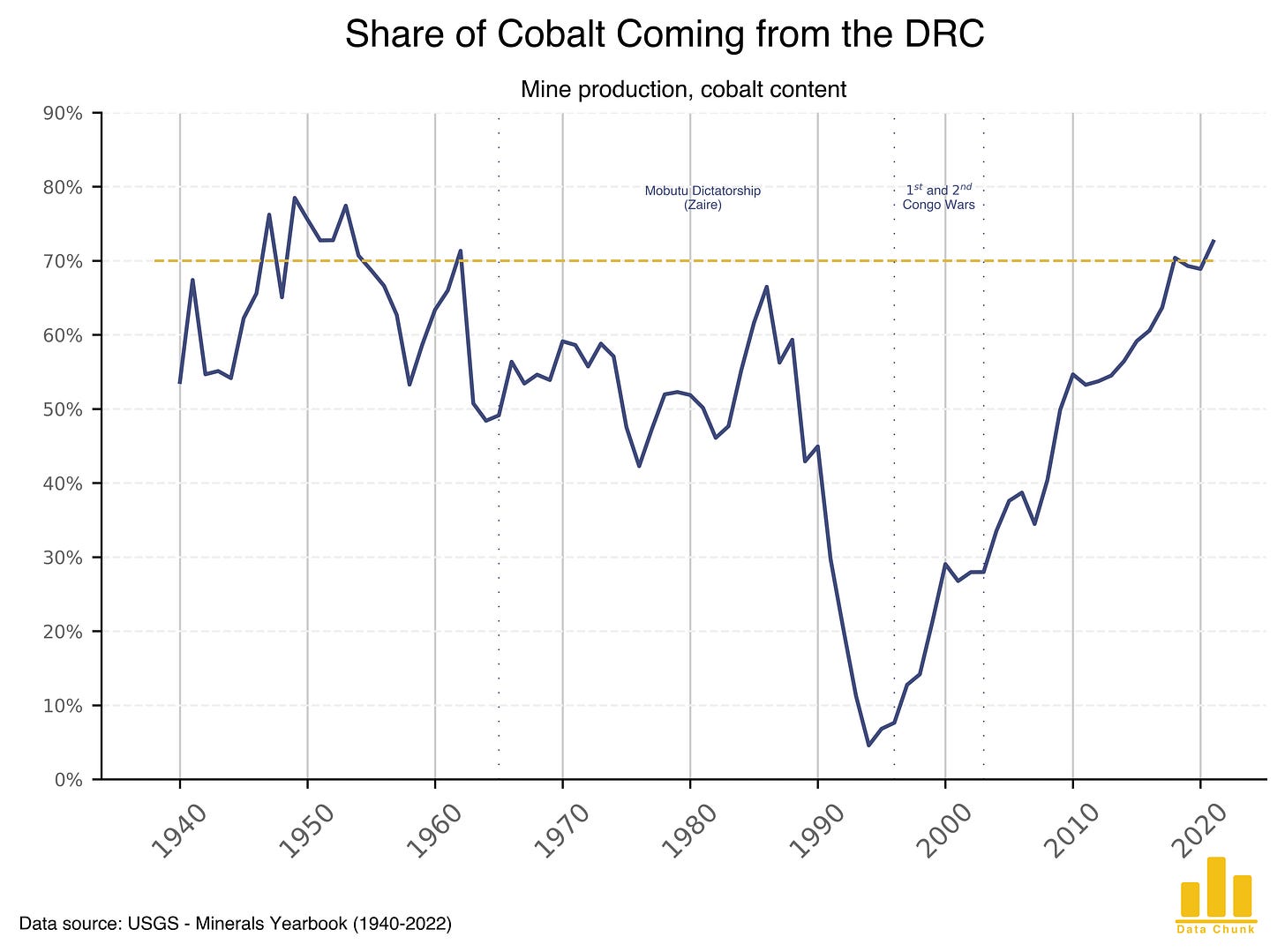

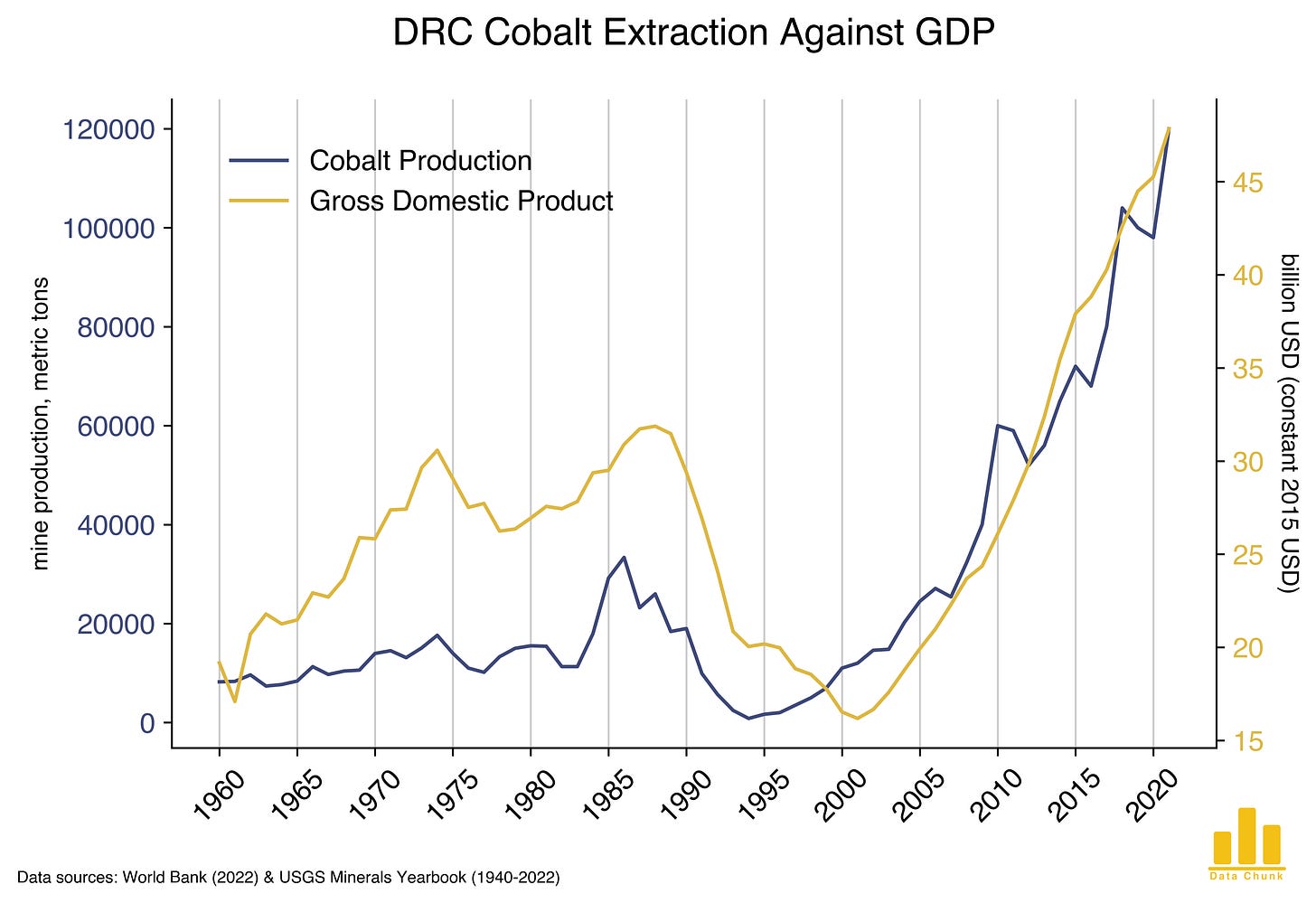

It is therefore no surprise that Congo has been the main supplier of raw cobalt for most of the past century, accounting for around 70% of world extraction:

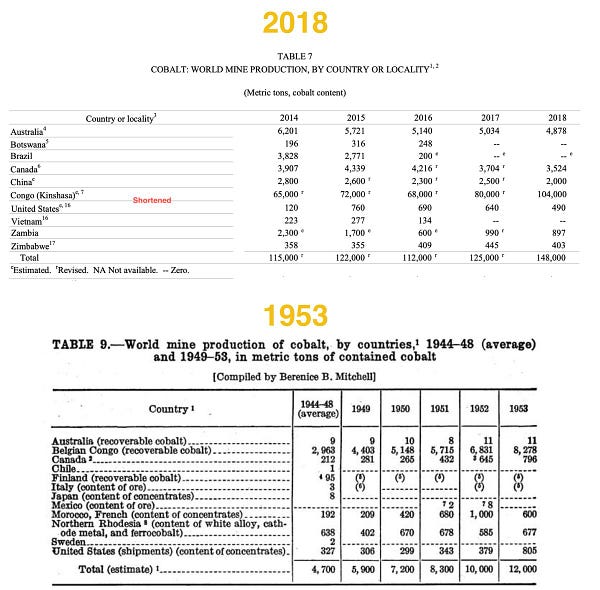

Behind the chart: The data come from the US Geological Survey from the years 1940-2022. The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s online library archive has all Minerals Yearbook from the USGS dating back to the 1930s. Those yearbooks include thorough comments and charts on metal extraction and the overarching industry in all world regions.

The data was unfortunately extracted manually by opening all scanned documents and looking for the right numbers. A lot of the numbers, especially before the 2000s are estimates, so beware that there might be discrepancies. The figures, however, provide a good understanding of the trends of development in the mining sector.

It is astonishing how little the mineral reports have changed over the years. This made working with the documents fairly straightforward.

The US Minerals Report on cobalt basically looks the same between 1940 and 2018 Almost the same table in the same spot with the same 5 years back of cobalt mined (although now up from 10K to 150K tons per year) Thank you, US bureaucracy <3 #datachunkThe charts and the information there, including formatting, varies very little between 1940 and 2020. The thing, however, that fluctuated the most, were the units of measure - from US tons (short tons), to pounds, to metric tons. Another fluctuation were the country names, which changed throughout history. The disintegration of the Soviet Union was the smallest problem. African countries (just like the centre character of this piece - Congo) have a fascinating recent history of colonialism, civil war and regime change which made the data extraction even more of a challenge.

We clearly see the enormous dependency we have built on the DRC’s cobalt extraction. The obvious problem is that prices fluctuate a lot based on Congo’s ability to meet the demand and on nickel and copper’s extraction as cobalt is obtained as a byproduct. On top of that, as seen through recent events (forcing most of Europe in a power saving mode of sorts), being heavily reliant on a single state with unstable politics could prove to be detrimental for a myriad of industries.

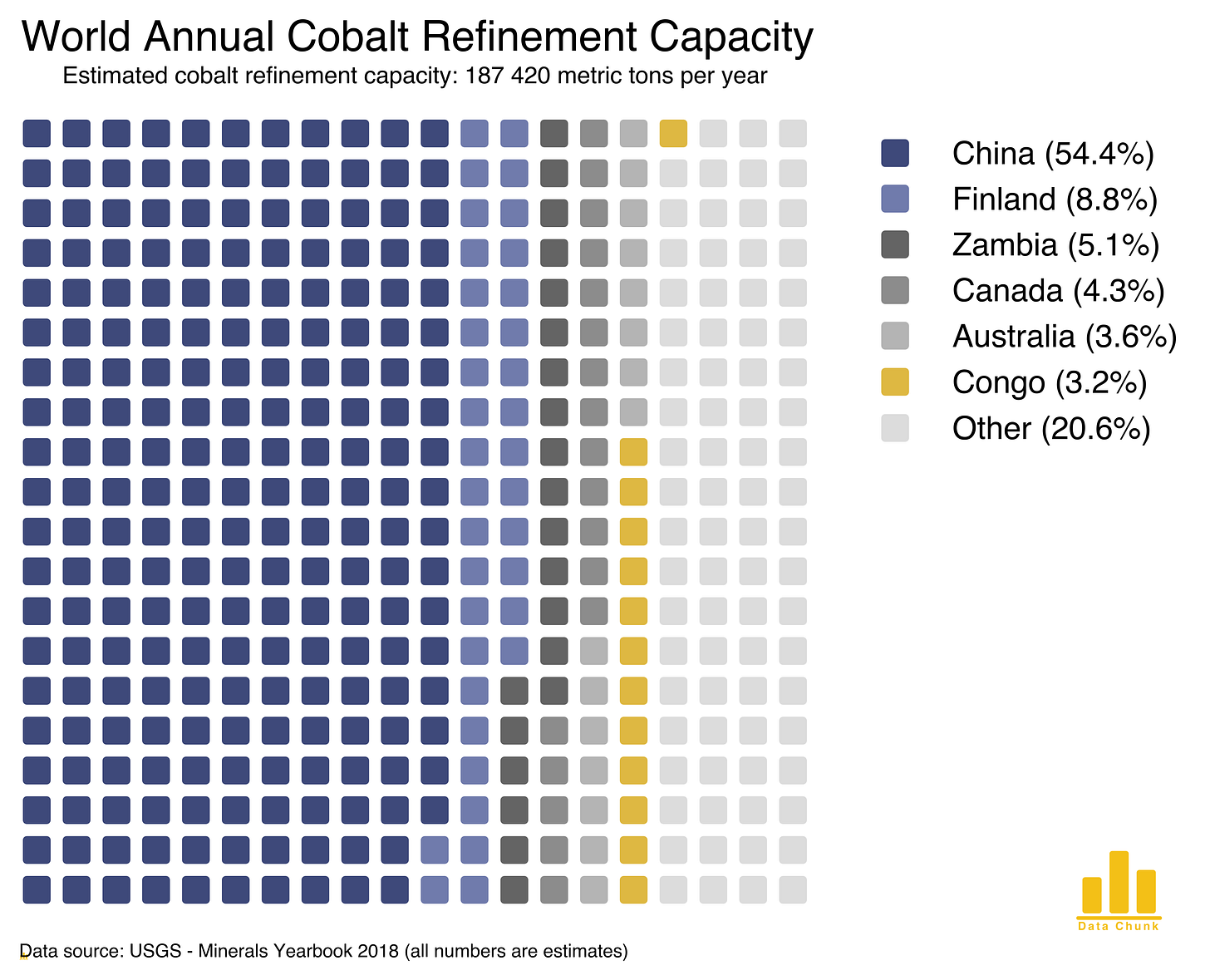

The DRC is, however, arguably the less prominent player in the chess game that electric vehicle production might become. China has been riding the cobalt wave for a while now. On the one hand taking control of mines, on the other by monopolising cobalt refinement.

According to S&P Global 70% of the DRC’s mining industry is owned by Chinese investors. Looking at 2018’s minerals report from the US Geological Survey, we can see that the mines with the largest cobalt extraction output are owned by companies with Western roots (Katanga Ltd., Mutanda Mining SPRL). Chinese investments within those, however, are harder to track. Still, there is quite a big direct Chinese presence. The DRC has also joined the Belt and Road initiative and taken loans and investments for its mining industry directly from China. The cobalt supply’s dependence on China is even more evident when we look at the world annual refinement capacity of cobalt:

Behind the chart: The chart above includes the six countries with the largest theoretical refinement capacity of cobalt. It is therefore not a guarantee that the available refineries are efficiently utilised.

The use of colour in such charts is fascinating. There are several key tasks I tried to accomplish with colour in this particular example: 1) We want to provide enough information on the top refiners and make them distinguishable, while 2) bringing extra attention to the biggest ones (China and Finland) by giving them more saturated colours than the others and also 3) highlighting the paradox that the largest extractor is not among the top refiners by using a contrasting colour.

This waffle chart was created using

pywaffle. The interface is very easy to use but not as customisable as I would have liked. Github link here.

Why isn’t the DRC refining its own cobalt, one might ask. After all, this would allow Congo to benefit from the soaring prices by selling cobalt directly without extra costs for transportation to China. The government clearly realises that and has mandated a ban on exporting unrefined cobalt. The catch is - miners do not have the capacity to refine their own metals and would rather get fast profits from selling directly to China. This is even more true among artisanal miners (miners who are “self-employed“, often mining by hand without much safety precautions), who often times risk their lives exactly because they expect fast profits. That is why there have been continuously numerous waivers on the export ban, making it in a sense obsolete.

Dealing with those supply chain issues is therefore one of the main concerns of most private companies in the industry as well as some developed countries.

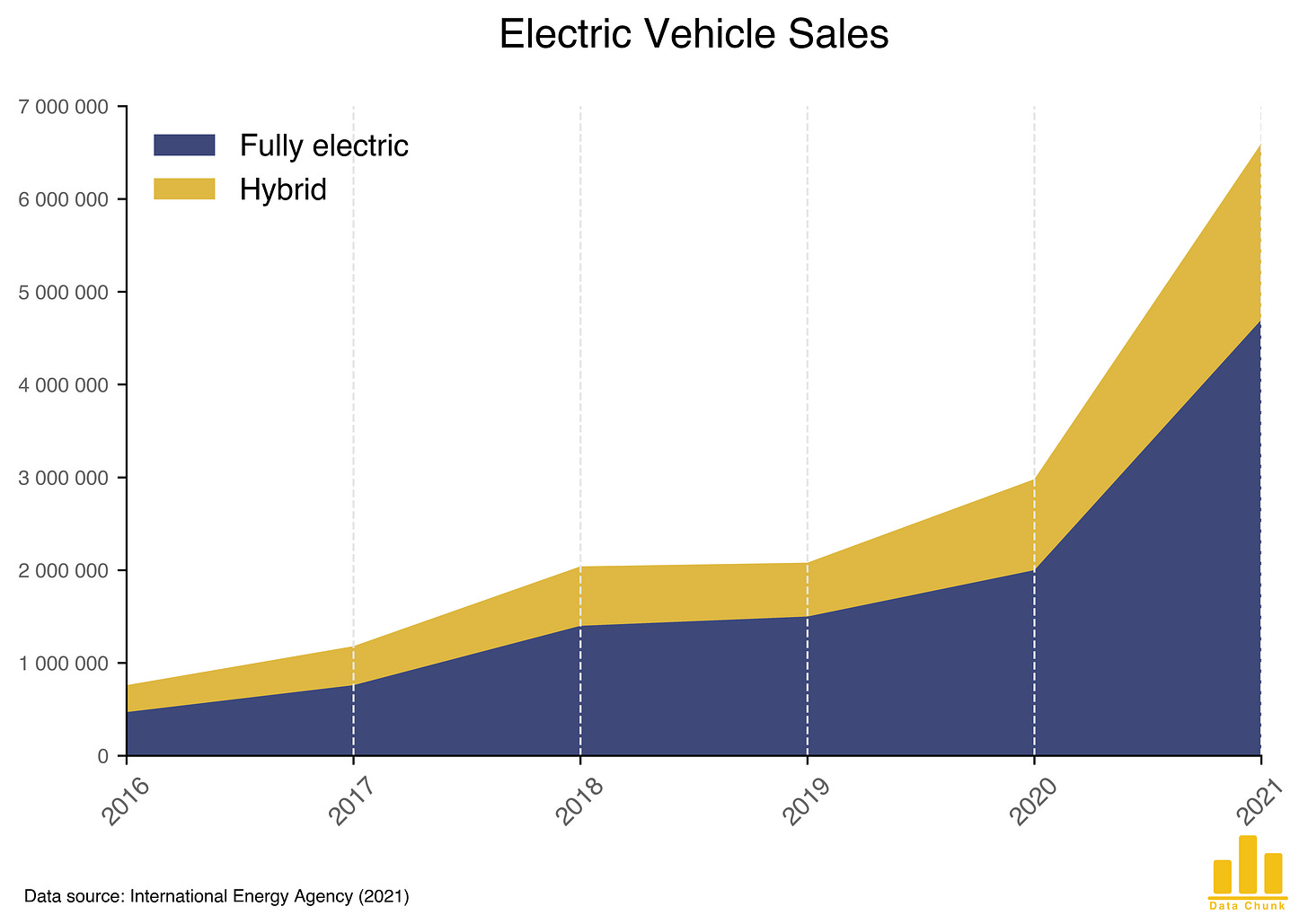

If questionable supply chains haven’t already convinced you that the cobalt economy is facing a problem that could get worse if not tackled and could spike the prices of some of your favourite gadgets, the demand side isn’t looking any more promising either - enter electric vehicles.

In the past years EV sales have been more than doubling on almost an yearly basis. This trend is not going away in the coming decades according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). They provide a more conservative scenario that assumes current EV and energy policies projecting shy of 28 million sales in 2030. If, however, all climate commitments made by governments were to be met, the IEA projects over 43 million sales in 2030.

There will be an enormous demand for batteries in the coming decades - be it for EVs, sustainable energy facilities or personal gadgets. It is also very likely that companies and governments will try to meet this demand. After all, extraction and refinement of cobalt have been increasing for the past decades. The question, however, is, at what cost is that happening.

B. The DRC and China’s Role in the Cobalt Economy

At that point of history it is relatively clear that depending almost fully on China is not a recipe for success. On the one hand the trade relations between China and the West have deteriorated with numerous sanctions coming from both sides. Questionable political moves (concerning the Taiwanese or the Uighur people, for example) may bring those sanctions on a whole other level in a matter of days. We are currently seeing how this is influencing energy prices among Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

On the other hand, Mr. Xi has proven that he would put the Chinese people and his vision of the future of the country above economic incentives. During (and arguably after) the Covid-19 pandemic China has suffered a lot economically by halting production and exports because of local lockdowns and strict contact tracing policies. The chip shortage of 2021-2022 is a prime example of over-reliance on the Chinese economy. The good news is that this has served as a lesson for a lot of companies and governments with silicone production in West being subsidised more and more among companies wanting to diversify their supply chain.

The DRC itself isn’t what would be considered a “stable“ market. The country has suffered a lot of political turmoil starting in the 1950s with its independence from Belgium. The country needed to build form the ground up when it comes to education, healthcare , infrastructure. In 1960 there were allegedly 16 people with university degrees among a population of 20 million. After Congo’s political crisis in the 60s, Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga rose to power bringing some political stability but enormous amounts of corruption at the same time. A huge amount of IMF and World Bank funds were embezzled by Mobutu, leading to the DRC (then Zaire) topping corruption indices. We can clearly see an economic decline, when it comes to cobalt, during that time in the first chart in this piece.

After several civil wars, inflation rates upwards of 550% in the 2000s and continuous government corruption, Congo has lost a lot of trust when it comes to Western investments, leaving the door open for Chinese funds. The economy is currently seeing an improvement, but it is still a hard recovery.

According to the Economist, around 15% of Congo’s cobalt is mined on a small scale by artisanal miners. More than one quarter of all mines involve child labour and horrendous incidents aren’t rare - falls, collapses, illness due to pollution. After all, when mining artisanally, there is little to no safety regulation on equipment and extraction methods. On top of that, stories of miners - artisanal and not - being exploited by the mine owners with unofficial taxes are also common. A lot of people having to rely on mining are forced to employ bribes or just accept whatever comes their way.

With people on the brink of poverty it is not inconceivable that many turn to artisanal and illegal mining, risking their lives or sending their children to unsafe mines. Around 60% of households rely on artisanal mining for their livelihood.

With all of this in mind the question arises of what do those people get in return for all of those potential risks. It is, of course, extremely difficult to get coherent data on an economic sector with so little regulation that resides to a great extent in the grey and black market.

The minimum wage in the DRC as of writing this article is 7 075 Congolese Franc per day which is around $3.44. The average wage could, however, be much lower than that (even around $1.20 per day) as Congo is one of the most impoverished African countries.

Having hard data on the miners’ wages, especially in the artisanal sector is nearly impossible. Some miners claim they can get up to $200 per week. According to Germany’s BGR around 40% of artisanal miners in Congo get less than minimum wage (which might be more than that average wage) with almost 10% getting upwards of $30 per day. This data was based on a 2019 survey of 240 artisanal miners.

The stakes are high when your family is on the brink of poverty, so it is not surprising that some people are ready to undertake huge health risks or even send their children to hazardous work sites for even the chance of getting a bit more food on the table. The fact of the matter is, Congo’s economy is unfortunately now partially reliable on those people risking their lives:

Behind the chart: GDP and cobalt extraction have an obvious correlation in the chart above (such of 84% according to Pearson's correlation coefficient).

How GDP is calculated: The expenditure approach to calculate GDP calculates spending by different economic groups. This is accomplished through this formula:

GDP = Consumption + Government Spending + Investment + Net Exports

Artisanal and illegal mining is not included (which would theoretically make Pearson's correlation coefficient even higher).

The following breakdown is speculation on the aforementioned correlation based on the expenditure GDP formula:

Starting backwards with the net exports, we have an economy that exports more than it imports - in 2021 according to the World Trade Organisation the DRC exported goods worth 23.5 billion USD and imported goods worth 10.3 billion USD. Exports are therefore a net contributing factor (of 13.2 billion USD of the DRC’s 54 billion USD GDP in 2021). According to the same source more than 74% of the exports were fuels and mining products. Most of that came from copper and cobalt (more than two thirds). The vast majority of cobalt comes as a by-product from large scale copper and nickel mining. This means that overall mining exports probably correlate heavily with cobalt mining.

Congo is not a particularly stable economy even for the African standard. Historically there has been a lot of instability and enormous amounts of corruption (during Mobutu’s dictatorship, for example). Investments are therefore not a huge component, but when they do happen it is likely that they are connected to the mining industry (with a large chunk currently coming from China).

Government spending is also likely to hugely involve the mining industries. As already shown in the chart above and in the EV demand chart, cobalt production and cobalt demand are continuously rising, so quite a lot of spending must be allocated to the mining infrastructure within the DRC.

Those are some of the reasons why cobalt has been a good predictor of GDP in the selected time period. The mining of the metal correlates well with most economic factors comprising the GDP, giving the economy of the DRC not a lot of diversity, which generally undermines economic stability.

If some of that speculation is true, Congo’s economy might take a huge hit in case the demand for cobalt lowers. That would mean less foreign investment, less mining subsidies overall as copper and nickel aren’t exactly exclusive to Congo.

Exactly because of this correlation all measures taken against the myriad of atrocities happening on legal and illegal mining sites should be well evaluated. Congo’s economy is a struggling one, that hasn’t shown very many assets outside of the mining industry. Reducing the cobalt demand, heavily regulating it or altogether working towards the elimination of cobalt in the EV supply chain without planning for a transition to some other asset may prove detrimental for the DRC, which is among the bottom 8 countries worldwide when it comes to GDP per capita (UN, 2020).

On a grander scale it is clear that cobalt is an important part of Congo’s economy and with the right government that income could contribute to diversification of exports. On an individual scale higher salaries (even from artisanal mining) do contribute to less poverty and maybe to some people being able to open a small local business and sustain themselves in a safer way.

It is therefore extremely important that a shift away from cobalt or a shift towards a more humane cobalt extraction is carefully planned and closely monitored and that the Congolese people is given an opportunity to sustain itself. It unfortunately looks like decisions, regulation and investments come from the West and China without much regard for the needs and wants of a much exploited economy. The DRC should plan a focus away from cobalt if it wants to secure a stable livelihood of its people.

With an ever growing demand and an unsustainable and inhumane supply chain, the question comes up of how we could improve the cobalt economy, end child labour and deadly mining conditions without wiping out Congo’s economic prospects.

C. The Future of Batteries and the Regulation Game

There are always multiple solutions to every problem, each with its own benefits and drawbacks. At this point it is hard to know what the right way would be. Here are, however, three distinct possibilities summed up in three words: regulation, innovation and Australia.

A lot of companies, including Tesla, have joined organisations such as Fair Cobalt Alliance which actively try to battle the human rights issues surrounding the cobalt economy. Manufacturers are doing that because of a multitude of reasons, and although simply caring for the third world and the children being exploited plays a part in the equation, I do not believe this is the only reason behind such efforts.

On the one hand, the average Western consumer is becoming more and more aware of what she is buying and where it comes from. This is, at the same time, being exploited to a certain extent. The marketing trick is becoming more popular - be it Apple losing the charging brick in the box of the new iPhones or H&M promoting its sustainable lines - and builds trust between the product and the consumer.

But what I think is even a bigger piece of this puzzle is the exact economic issues that came up earlier in this piece: the supply chain is currently heavily reliant on the DRC and China and this is no recipe for a reliable growth as it leads to higher prices and higher risk for companies. The decision makers in larger corporations are perfectly aware of this and its potential consequences - it’s a ticking time bomb.

But no matter how egoistic or philanthropic the incentive might be, this is a step in the right direction when it comes to the environment and the numerous human rights violations surrounding the metal extraction industry. Companies are now actively trying to track the source of their cobalt so that they have more knowledge and control over the process.

As you can imagine, however, in a chain consisting of artisanal miners, Chinese mine owners and a monopoly on refinement it is hard to know the origin of all raw resources. At the same time with the surging demand of batteries and manufacturers wanting to avoid situations such as the post pandemic chip shortage, it might also prove more profitable for some to shut their eyes to that and move on.

Another very pursued approach is replacing cobalt with another metal altogether. Most of Tesla’s standard range Model 3 and Model Y are currently using LFP batteries.

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP - the F coming from “ferrum”) batteries have a lower energy density, meaning that the range is noticeably lower. They are not only used in short range consumer EVs, but in public transportation busses as well. Those batteries are generally a lot cheaper (because iron is more abundant and easier to mine). The production, however, is still China-dominated, which isn’t ideal. Other solutions are being developed such as NFA batteries (Nickel Iron Aluminium), but currently aren’t widely available on the market.

The approach of building a better battery that offers competitive range at a fair price with minimal supply chain issues has several disadvantages as well. For once, if we were to find a perfect replacement tomorrow (which doesn’t exactly seem to be the case), the DRC’s economy would take a huge hit, as we already explored in the previous section. From a technical standpoint such a battery is currently harder to produce technically and potentially more chemically unstable.

The last point that I am going to bring up in this article involves a land far away that has been staying under the radar when it comes to cobalt extraction. Australia might be a promising player who can diversify the supply chain with better regulations and humane extraction.

The industry is unfortunately very underdeveloped (delivering around 3% of the cobalt mined, while the reserves lie at 18% of world cobalt capacity) and if the tendency of going off of cobalt continues, it might not be the best decision to start investing in the sector now. It would, however, ensure more stability in the market of a metal with clear benefits when it comes to battery capacity and stability.

A bigger problem might be the amount of certification needed to be done. While 1.4 million tons of cobalt are estimated to be on Australian territory, only 560 thousand are Joint Ore Reserves Committee-compliant or equivalent, meaning that it is considered extractable according to the JORC standards. Furthermore, the cost of mining will obviously be greater because of the higher safety standards and wage regulations. However, having more diversity in the supply chain, especially in a relatively stable country, both politically and economically, could prove to be a viable strategy.

Another potential up and coming player, as seen on the chart above, is Indonesia. The country is already the world’s largest nickel producer and has some sizeable cobalt reserves - both metals crucial for the lithium ion battery. With the country’s focus on batteries, the already present mining infrastructure and the ambitious efforts of the current government, we might be seeing an increase in cobalt production as well.

Conclusion

The 2022 energy crisis is a valuable lesson of the importance of a healthy supply chain. The West needs to stay a few steps ahead and manage such dependancies better as not to be reliant on Chinese, Congolese, Russian, Saudi Arabian politics. At the same time I do believe that responsibility lies not only the DRC to diversify its economy, but also on the West. The Western economies currently dictate what is a valuable resource and this leaves some countries at risk of becoming too reliant on those trends. It is therefore important to think not only about the current problems we face - be that an energy crisis making us go sign contracts with the Saudis or a cobalt supply chain issue making us come up with alternative battery solutions. It is necessary to see the big picture with its consequences and try to optimise for them all - for the sake of our Teslas, but also for the people of Congo.

This article is the first one published on this blog and it came to existence out of pure personal interest in the topic. It was originally inspired by the article of The Economist. I did the research and coding in my spare time. I am not an expert on the topic and have no experience in writing, so there might be certain factual mistakes.

The post is not monetised or sponsored in any way and reflects my own current, non expert opinions, which may change in the future. If you have any feedback, please send it my way.

Best, Boris